What do artisanal cheese and maple syrup have in common? In North America, and elsewhere too, they’re likely to bring to mind the state of Vermont, which produces more of both than anywhere else. They’re also the research focus of Amy Trubek at the University of Vermont, a trained chef and cultural anthropologist. Trubek gave […]

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 22:46 — 31.4MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | | More

What do artisanal cheese and maple syrup have in common? In North America, and elsewhere too, they’re likely to bring to mind the state of Vermont, which produces more of both than anywhere else. They’re also the research focus of Amy Trubek at the University of Vermont, a trained chef and cultural anthropologist. Trubek gave one of the keynote speeches at the recent Perugia Food Conference, saying that terroir – which she translates as the taste of place – combines two elements. There is the taste itself, which when people talk about it with one another becomes a social experience that, she said, lends meaning to eating and drinking. And it is “a story we tell to assure that our food and drink emerges from natural environments and conditions.” Vermont cheese, at least the lovingly crafted artisanal kind, as much as maple syrup, reflects those concerns with natural environments and conditions.

What do artisanal cheese and maple syrup have in common? In North America, and elsewhere too, they’re likely to bring to mind the state of Vermont, which produces more of both than anywhere else. They’re also the research focus of Amy Trubek at the University of Vermont, a trained chef and cultural anthropologist. Trubek gave one of the keynote speeches at the recent Perugia Food Conference, saying that terroir – which she translates as the taste of place – combines two elements. There is the taste itself, which when people talk about it with one another becomes a social experience that, she said, lends meaning to eating and drinking. And it is “a story we tell to assure that our food and drink emerges from natural environments and conditions.” Vermont cheese, at least the lovingly crafted artisanal kind, as much as maple syrup, reflects those concerns with natural environments and conditions.

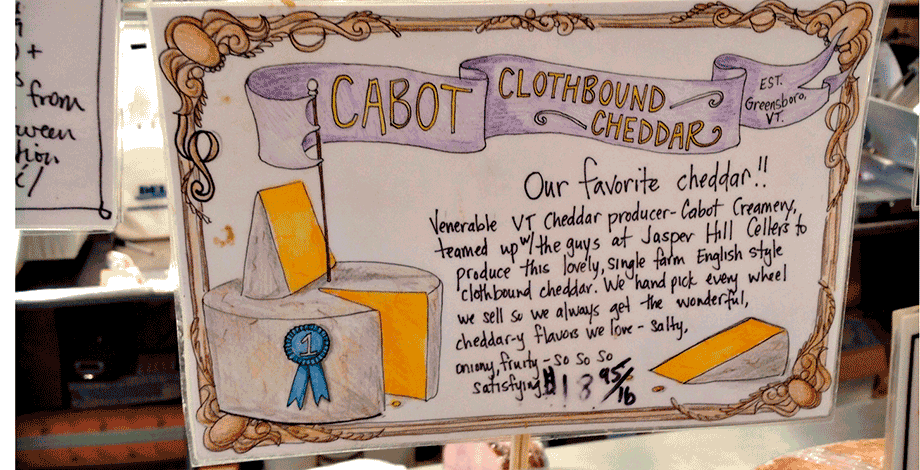

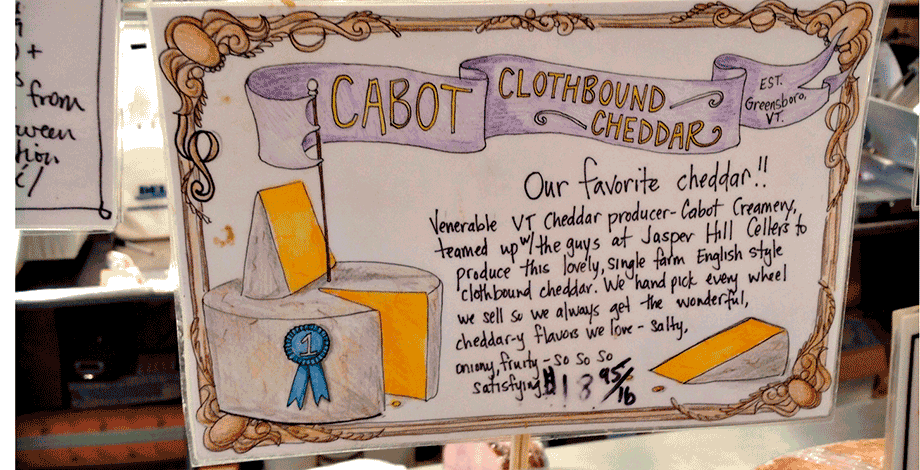

In our interview, we didn’t dwell too much on the scientific research underpinning Amy Trubek’s ideas. I found the idea that simply knowing the personal story of a cheese – who makes it, where, why – can influence how you respond to it fascinating. Taste, surely, is physiological. How would the story affect that? But it does. In one study of four different cheeses, people heard either a generic story about that cheese category, taken “from dairy science manuals,” or “socially and contextually relevant production information”. No matter how much they actually liked the cheese, or their “foodiness” on an established scale, people who had been told personal stories about the cheesemakers liked the cheese more than those told about the cheese alone. (See Note 3 below.) What’s more, according to Rachel DiStefano, who did a Master’s thesis with Amy Trubek, cheesemongers are vital allies in telling the stories and thus helping consumers to value artisanal cheeses.

By contrast, terroir for maple syrup does seem to be less about personal stories and more about the soils the trees are in and the details of turning sap into syrup. Trubek has worked with a large, multidisciplinary team to create new standards and vocabulary that take discussions well beyond “sweet”. And yes, there is some evidence that soil does affect taste:

[S]yrup produced from trees on limestone bedrock had the highest quantities of copper, magnesium, calcium and silica, which scientists hypothesized had a role in the taste. Shale syrups came in second in all of these substances, followed by schist.

A final thought: Amy Trubek’s throwaway remark about fake maple flavour sent me down an internet rabbit hole that in the end proved surprisingly productive.

Notes

- The 2nd Perugia Food Conference Of Places and Tastes: Terroir, Locality, and the Negotiation of Gastro-cultural Boundaries took place from 5–8 June 2014. It was organized by the Food Studies Program of the Umbra Institute.

- Sign photograph by Katherine Martinelli.

- Consumer sensory perception of cheese depends on context: A study using comment analysis and linear mixed models.

- Rachel DiStefano has written about her field work, behind the counter of a specialist cheese shop in Cambridge, Ma.

- If you’re entertaining thoughts of maple syrup expertise, you’ll need to study the new sensory maps and be able to talk knowledgeably about the history of sugaring.

- Other images by Rachel DiStefano.

The history of pasta, ancient and modern, is littered with myths about the origins of manufacturing techniques, of cooking, of recipes, of names, of antecedents. Supporting most of these is a sort of truthiness whereby what matters most is not evidence or facts but – appropriately for us – gut feeling. Combine that with the echo chamber of the internet, and an idea can become true by virtue of repetition. So it is, by and large, for the idea that Arabs were responsible for inventing dried pasta and for introducing it to Sicily, from where it spread to the rest of the peninsula and beyond. You can find versions of this story almost everywhere you look for the history of dried pasta.

The history of pasta, ancient and modern, is littered with myths about the origins of manufacturing techniques, of cooking, of recipes, of names, of antecedents. Supporting most of these is a sort of truthiness whereby what matters most is not evidence or facts but – appropriately for us – gut feeling. Combine that with the echo chamber of the internet, and an idea can become true by virtue of repetition. So it is, by and large, for the idea that Arabs were responsible for inventing dried pasta and for introducing it to Sicily, from where it spread to the rest of the peninsula and beyond. You can find versions of this story almost everywhere you look for the history of dried pasta.

What do artisanal cheese and maple syrup have in common? In North America, and elsewhere too, they’re likely to bring to mind the state of Vermont, which produces more of both than anywhere else. They’re also the research focus of

What do artisanal cheese and maple syrup have in common? In North America, and elsewhere too, they’re likely to bring to mind the state of Vermont, which produces more of both than anywhere else. They’re also the research focus of