Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 18:04 — 16.7MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Android | RSS | More

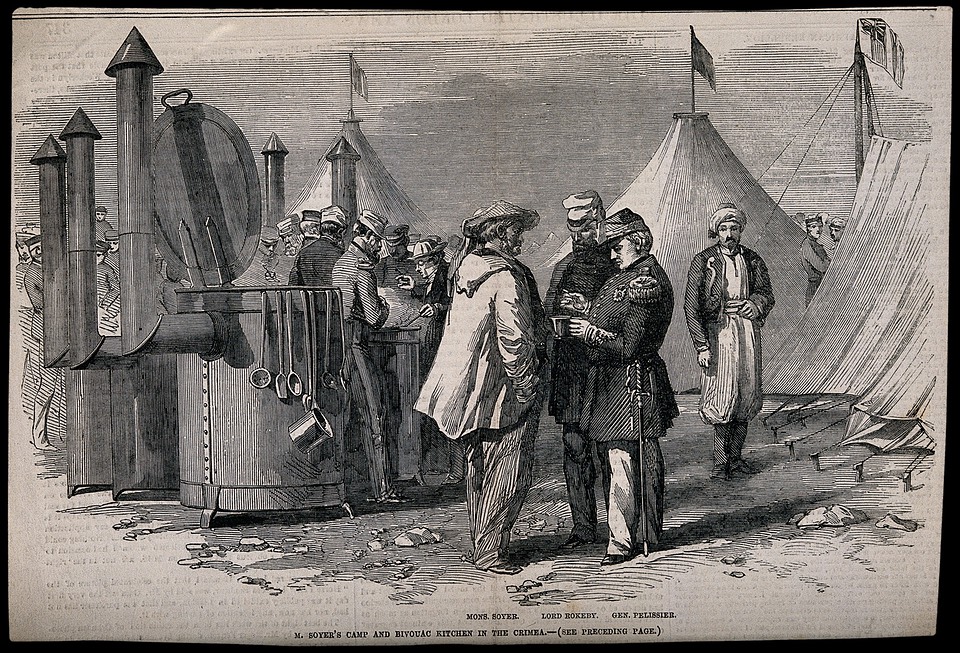

Alexis Soyer was perhaps the greatest chef of Victorian England. He designed the most modern kitchen of the 1840s and equipped it with many of his own inventions. He cooked unimaginably luxurious — and expensive — dinners for royalty and the aristocracy. He also built soup kitchens for the poor and his Famine Soup fed hundreds of thousands of destitute people in Ireland. His cookbooks sold in the hundreds of thousands, and sauces bearing his name brought luxury to the middle classes. He transformed British army cooking during the Crimean War, and the stove he invented for Crimea was still in use in the Gulf War in 1982. During the Crimean War, people said his name would live alongside Florence Nightingale’s. It didn’t, although lately Soyer, one of the first celebrity chefs, is being rediscovered.

Alexis Soyer was perhaps the greatest chef of Victorian England. He designed the most modern kitchen of the 1840s and equipped it with many of his own inventions. He cooked unimaginably luxurious — and expensive — dinners for royalty and the aristocracy. He also built soup kitchens for the poor and his Famine Soup fed hundreds of thousands of destitute people in Ireland. His cookbooks sold in the hundreds of thousands, and sauces bearing his name brought luxury to the middle classes. He transformed British army cooking during the Crimean War, and the stove he invented for Crimea was still in use in the Gulf War in 1982. During the Crimean War, people said his name would live alongside Florence Nightingale’s. It didn’t, although lately Soyer, one of the first celebrity chefs, is being rediscovered.

Notes

- Ruth Brandon’s book The People’s Chef has different subtitles in different places. You should be able to find a copy.

- Frank Clement-Lorford maintains a website dedicated to Alexis Soyer, where you can get his book and read, for example, about the restaurant, Soyer’s Universal Symposium of all Nations. There’s a more academic account by April Bullock in Gastronomica.

- Many people who write about Soyer try to reproduce his recipes. Lost Past Remembered shares some history of the Reform Club with a version of Soyer’s famous grouse salad.

- Hot on the Trail by Thomas A.P. van Leeuwen contains a few errors of fact but is good on Soyer’s inventions. Forgotten history – Soyer’s Stoves offers a more military perspective on his stoves.

- Music by Podington Bear. Images from the Wellcome Trust.